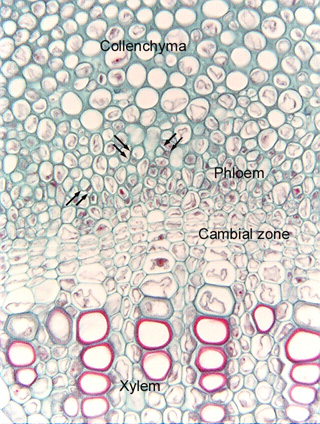

Fig.

8.1-4a. Transverse section of vascular bundle in clover stem (Trifolium).

In many dicots, phloem is difficult to examine because the cells are very narrow

and there is no really obvious pattern as in monocots. Typically, the

first place to look for dicot phloem is just to

the exterior of xylem -- there will be a group of cells that are too

small and cytoplasmic to be cortex parenchyma. Then, look

for pairs of sieve tube members and companion cells: one very small,

very cytoplasmic cell and one larger, empty-looking cell (three sets are

indicated by pairs of arrows). There is a good chance that you have found the

sieve tube members and the companion cells, but in many cases, it will be

difficult to be absolutely certain. With luck, the companion cell will appear to

be a sister cell to the sieve tube member, basically, it will appear to be just

a corner or side of the sieve tube member that has been cut off to be a separate

cell. But the three companion cells here do not have that appearance.

Fig.

8.1-4a. Transverse section of vascular bundle in clover stem (Trifolium).

In many dicots, phloem is difficult to examine because the cells are very narrow

and there is no really obvious pattern as in monocots. Typically, the

first place to look for dicot phloem is just to

the exterior of xylem -- there will be a group of cells that are too

small and cytoplasmic to be cortex parenchyma. Then, look

for pairs of sieve tube members and companion cells: one very small,

very cytoplasmic cell and one larger, empty-looking cell (three sets are

indicated by pairs of arrows). There is a good chance that you have found the

sieve tube members and the companion cells, but in many cases, it will be

difficult to be absolutely certain. With luck, the companion cell will appear to

be a sister cell to the sieve tube member, basically, it will appear to be just

a corner or side of the sieve tube member that has been cut off to be a separate

cell. But the three companion cells here do not have that appearance.