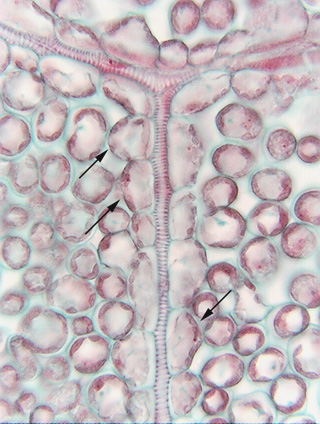

Fig.

3.5-3. Paradermal section through the leaf of ground ivy (Glecoma,

in the mint family, not a real ivy). The long strands with helical red bands are

xylem cells that conduct water. At this point, focus on the larger, rounded

parenchyma cells that touch the conducting cells (arrows indicate three of

many). The conducting cells are

slightly scalloped because the parenchyma cells pressed so firmly against them

while they were maturing. The dark material in all the parenchyma cells are

chloroplasts packed so closely that it is difficult to tell that they are

individual bean-shaped organelles. In parenchyma cells that contact xylem

conducting cells, chloroplasts are located along the walls away from the

conducting cell. This leaf – like most material used for general studies of

plant anatomy – was prepared by embedding it in wax and then cutting it into

sections about 10 to 12mm

thick. This is too thick to be able to see labyrinthine walls, but almost

certainly, the parenchyma cell walls that touch the xylem conducting cells are transfer

walls with labyrinthine walls. To be certain, it is necessary to use

either scanning or transmission electron microscopy. If these cells do indeed

have labyrinthine walls, then they are transfer cells.

Fig.

3.5-3. Paradermal section through the leaf of ground ivy (Glecoma,

in the mint family, not a real ivy). The long strands with helical red bands are

xylem cells that conduct water. At this point, focus on the larger, rounded

parenchyma cells that touch the conducting cells (arrows indicate three of

many). The conducting cells are

slightly scalloped because the parenchyma cells pressed so firmly against them

while they were maturing. The dark material in all the parenchyma cells are

chloroplasts packed so closely that it is difficult to tell that they are

individual bean-shaped organelles. In parenchyma cells that contact xylem

conducting cells, chloroplasts are located along the walls away from the

conducting cell. This leaf – like most material used for general studies of

plant anatomy – was prepared by embedding it in wax and then cutting it into

sections about 10 to 12mm

thick. This is too thick to be able to see labyrinthine walls, but almost

certainly, the parenchyma cell walls that touch the xylem conducting cells are transfer

walls with labyrinthine walls. To be certain, it is necessary to use

either scanning or transmission electron microscopy. If these cells do indeed

have labyrinthine walls, then they are transfer cells.